426

●

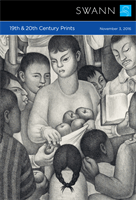

DIEGO RIVERA

Fruits of Labor

.

Lithograph, 1932. 417x298 mm; 16

1

/

2

x11

3

/

4

inches, full margins. Signed, dated and

numbered 70/100 in pencil, lower margin (the edition numbers erased and rewritten). A

superb, richly-inked impression of this very scarce, important lithograph.

Diego Rivera (1886-1957), who helped establish the Mexico Mural Movement and was

a leading artistic figure in Social Realism, was born in Guanajuato in North-Central

Mexico. His well-to-do family encouraged his artistic avidity from a young age; his parents

installed chalkboards and canvases around the house after coming home one afternoon to

find the walls covered in their toddler’s drawings. In 1897, Rivera began studying at the

oldest art school in Latin America, the Academy of San Carlos in Mexico City (now the

Escuela Nacional de Bellas Artes). He remained until 1907 (three years before the start of

the Mexican Revolution) at which point he left for Europe to continue his studies. Rivera

spent the better part of the next 14 years abroad, mainly in Paris, where he was deeply

involved in the thriving avant-garde art scene. Rivera was submerged in the artistic circle

in Montparnasse and was friends with Amedeo Modigliani, who painted several portraits

of him in 1914.

Despite his absence from Mexico, Rivera intently followed the political situation at home.

The Mexican Revolution officially ended in 1920, after a decade of bloodshed and

political upheaval.The new government, led by Álvaro Obregón, decided to utilize art as

a vehicle to unify society and promote their values of equality. Rivera was recruited for

this effort; the Mexican government prompted him to first take a tour of Italy to study

Renaissance frescoes (this classical influence is easily detected in his work) and then to

return to Mexico as a muralist.The country’s Minister of Education commissioned local

artists, among them Rivera, to create murals around Mexico City to celebrate the lives of

the working class and the indigenous people. Rivera embraced the projects and, as a result

of them, quickly gained recognition and prominence as a leading muralist in Mexico.

Rivera was simultaneously garnering the attention of the Soviet Union for his outspoken

support of Communism. In 1928, while in Russia on an invitation from the government,

Rivera met and befriended Alfred J. Barr, future director of The Museum of Modern Art.

This friendship, as well as the admiration and patronage of Abby Aldrich Rockefeller, an

avid collector of his work and one of the founding members of the museum, led to

Rivera’s one-man show at MoMA in 1931, an event that brought the artist into the

American mainstream. Rivera created five “portable murals” specifically for the exhibition,

completing them in the six weeks between his arrival in the city and the exhibition’s

opening. The show caused a buzz with the press and was a huge hit with the public,

solidifying Rivera’s status in America. His work was so well received that he completed

three additional murals of New York scenes after the show’s opening and received

numerous additional mural commissions across America (notably the Detroit Industry

Murals, 1932-33, for the Ford Motor Company).

Carl Zigrosser, director of the Weyhe Gallery and advocate of modern Mexican art, met

the artist while he was in NewYork for his MoMA show. Zigrosser recognized the Rivera’s

rising popularity and encouraged him to embrace lithography as a way to capitalize on

his success and disseminate his art. Imagery used in his murals inspired (and in some cases

was replicated in) his prints, such as meditations on his heritage and identity, Mexican

history, political strife and the celebration of the working class. Rivera also made several

intimate portraits of his then-wife, Frida Kahlo.The artist created only fourteen prints in

his entire career, mainly lithographs published by the Weyhe Gallery, as well as one

linoleum cut in the late 1930s in Mexico.

[15,000/20,000]